Emergent Cinema

When Roger Ebert famously wrote that Video Games could never be art, many criticised his ideas and tried to convince him of the opposite, and they mostly tried to convince him about the way games could bring great stories to life.

They cited the amazing emotional punch of Ico; and the storytelling depth of games like Final Fantasy VI or VII, or Planetscape: Torment. They tried to make him realise that some games can bring the player into stories, narratives, and experiences just as great as any movie, novel or song. And he didn’t buy into the idea, at all. He was convinced that the simple fact that the player of a game could alter the intention of the creator was proof that it could never be considered real art.

Few of them tried to point out that games are an art form for reasons that have nothing to do with storytelling. How most of what makes this specific medium sing is system building, level design, and interaction design. Sometimes, they also tell stories. Sometimes, they embrace all media into one in ways that could have never been dreamt of by artists twenty years ago.

It’s a bit like Katamari Damacy: a small creature rolls around and everything around it sticks to it and grows into a massive ball. Art, sometimes, works like that.

Cinema is a language that takes the rhythmical aspects of music, the pictorial grammar of photography and painting, and the narrative structures from theatre and literature, and rolls them into something new. Video Games go a step further, and add interactivity to this - a way to control time, action, and the order of things.

Languages cross over all the time, and two recent games - Immortality and Alan Wake 2 play with cinema in ways that a lot of movies rarely have a chance to.

SEMI DISCLAIMER: in this article, I will use the word “Cinema” to describe a language: the language of images and sounds set to rhythm, either with the use of editing, or staging. This language is commonly used to make movies, but it is not married to that format. It can be used in TV shows; home videos; commercials; music videos; and, of course, video games.

PART I: IMMORTALITY

Immortality, by Half Mermaid, explores the career of Marissa Marcel, an actress who has shot three movies in her whole life, across three different decades, and none of those films have ever seen the light of day. Marcel's past and disappearance are the mystery that the player needs to explore and solve by browsing through a large selection of raw footage from Marcel's unfinished films, and some behind-the-scenes footage.

The interface of the game resembles a classic film editing bay (a moviola), in which the player can select different scenes, and pause any frame of them. Once paused, different parts of the scene can be interacted with: if a scene features some actors and some props, let's say a glass and a knife, each of those elements can be clicked on, and they will "transport" the player to another random scene featuring a similar prop or the same actor. As the player keeps doing this, they unlock more and more scenes, and will slowly get to know more and more of Marcel's past, and slowly unravel her mystery.

Is in this structure that Immortality becomes a very fascinating exploration of cinema. Cinema is a time-based language; a series of audiovisual conventions that, strung in time, allow to bring to life almost anything, from abstract ideas to recreation of reality to stories. More than visuals and sounds, cinema, like music, is defined by its relationship with rhythm. Pacing is determined by many things, but most of all, by the craft of editing: people often connect the world "cinematic" to visual characteristics (a certain colour scheme, moody images with massive depth of field), but "cinematic" is something that happens when the layering of separate elements creates a specific audiovisual groove. Sequencing, and the manipulation of time, are the keys to cinema.

The fascinating idea behind Immortality is that it puts the player in control of that crucial element, at least to some extent. They have access to a massive amount of clips, and most of the time, it’s not easy to tell where they are supposed to fit in the movie they have been shot for. Often, the slate for each scene can give us a sense of where the scene is supposed to fit in the sequencing of the movie, and some seem to be missing. While we are not given all of the footage to put together the three movies, we get a decent approximation of what an editor usually works with when assembling one. Cunningly, the moments before and after a take are also used to tell a bigger story, one that helps the player piece together a mystery that spans decades, a meta-narrative that can be pieced together from hundreds of clips.

The interesting thing in discovering those scenes is that it becomes a sort of cinematic autopsy: if Cinema uses rhythm to merge its elements, to cook them into a meal, the player here plays with the ingredients. Each scene has its internal rhythm, of course. We are often reminded that camera movement, staging, and even changes in dynamics from the actors can create flow just as much as cutting does; but, ultimately, is the player that is in control of the pacing of the narrative - with some help from randomness.

There are hundreds of scenes to discover, but the order in which they will be discovered is not fixed; the same image can link to different other scenes, randomly, creating an emergent narrative that will be unique to each player. That is the kind of narrative that video games excel at emergent narrative.

This is, by the way, one of the main reasons Ebert declared that video games could not be art: because the author has no way to “force” the player to follow a set path while also giving them a chance to interact with the narrative. Immortality, like many games before it, is a great example of how unfunded this worry was: one can build a narrative specifically to be experienced in many different ways, and that takes a great amount of artistry. What Barlow and his team of writers, artists and performers have done is strike an impressive balance between building scenes that can believably fit in a standard movie while also having them imbued with the kind of ambiguity, thematic poignancy and openness to connect in multiple ways.

It’s not rare to discover a string of scenes, randomly sequenced, from each one of the three different movies, yet to feel like that order makes perfect sense in highlighting a theme, or a hidden character arc. There is no way the creators could have anticipated every possible combination between so many scenes, but the writing has taken into account the magical power of editing to create meaning from sequencing even when unintended. The performances do the same: there is a really magical quality in the performances from the leads - Manon Gage and Charlotta Mohlin - that allows scenes from different movies, different eras, and even behind-the-scenes moments, to feel unique to that context, yet also fit to a wider one,

Eventually, discovering some key ones brings the game to an "end", that signals that the players have found enough material to uncover its mystery. The way this happens is sort of mysterious, and the randomness behind this makes each playthrough extremely different from others. This means that for some people the game lasts about six hours, and for others, it can take more than ten, and become a bit repetitive, at times. Emergent design is tricky that way.

The interesting thing about Immortality is that by using the world and the process behind the making of feature film as its backdrop it manages to highlight and deconstruct cinema in ways that are built around curiosity and fun rather than as some sort of intellectual exercise.

PART II: ALAN WAKE 2

Remedy Entertainment has always aimed to blend various forms of media since their first hit, Max Payne, mixing video games, radio dramas, and comic books. The first Alan Wake brought live-action footage into the mix, as well as literature, and songs specifically crafted for the game as a way to enrich world-building as a form of storytelling. The company kept experimenting with mixing these elements with Quantum Break and Control. Alan Wake 2 is their most confident attempt yet to make all of these elements work together. It mixes different media with an extraordinary level of care.

Skeuomorphism and video games go very well together

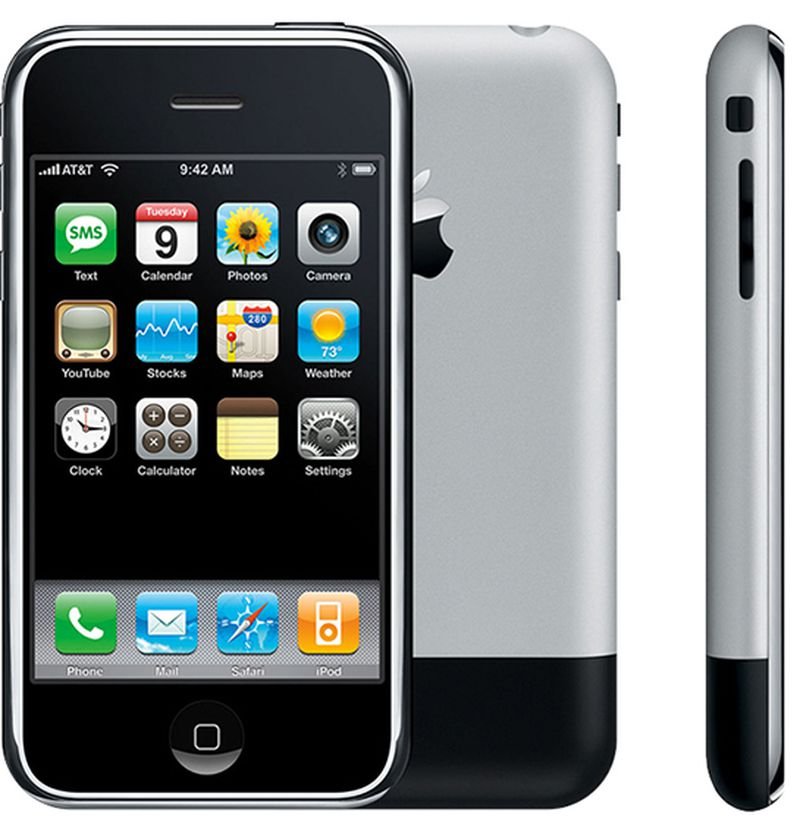

I really liked the look of the first iPhone and iPad operating system. Icons were meant to mirror physical objects: the Notes app felt and looked like a paper notebook; Books had page-turn animations like actual books. The YouTube app had an icon that looked like an old CRT TV set.

Remedy and Half Mermaid both use elements of Skeuomorphism - a school of design that uses real-life objects as inspiration for digital interfaces. Designers are seldom fans of this approach - considering it tacky and lazy, preferring more minimalistic, sleek approaches to representation that do away with any relationship with physical objects. But in video games, this approach can add to the player’s immersion immensely.

Alan Wake 2 and Immortality embrace skeuomorphism aggressively. In AW2, the player seldom navigates through regular menu screens. When playing as Saga Anderson, one of the two protagonists, a large part of the action revolves around collecting evidence and testimonies about the mysteries at the centre of the narrative, and that investigative work takes place in a “mental projection” of Saga’s office, equipped with a massive corkboard to string together clues, character files, recordings, manuscripts. When playing as Alan Wake, the player can enter a projection of his writing space, where they can place together narrative ideas on a massive board and write a new version of the game world. The designers could have allowed the player to access the same gameplay tools in through minimalistic, easy-to-navigate menus.

But by choosing to represent physical spaces, filled with pictures, papers, writing tools and furniture, they give much more consistency to the reality of the characters. This interface does not pause the game, it’s meant to never break immersion in the game world, even if that means sacrificing ease of use and practicality. Immortality’s interface is also based around its fiction: the “moviola” where the player navigates and discovers new film reels from Marcel’s projects has a tactile quality that enhances the immersion in the game world. This “diegetic first” approach is something that could put off some players who are more interested in pure mechanics, the ability to quickly navigate around information, and move forward in the game.

But video games are a lot like delayed improv. The designers set up a scenario for the player to react and add to, allowing for different approaches. The player needs to commit to that. To play is not just to interact with the world and solve its challenges, but to some extent, it’s also about buying into the fiction enough to accept its rules and play together with its rhythms, its texture, its mood. These two games are best enjoyed if approached, to some extent, as Role Playing Games - not mechanically, but in approach and intention.

Mixing Media

After the first Alan Wake, Remedy published Quantum Break, a game that committed so hard to mixing different media to produce an entire TV show that would play in between chapters of the game. Sam Lake, Remedy’s creative director, has shared how hard that experience had been: video game design is an iterative process, that requires constant trial and error; filmmaking is mission-critical, a large amount of planning culminates in a very compressed production time where a large amount of people comes together to work on a project that is quite hard to organise again. This means that the filmed parts of the game dictated “locked” the game designers’ possibilities, and made the design process awkward, to an extent.

After this experience, Remedy has shifted its approach. With Control, they have inserted live-action footage as diegetic elements in the game, as videos you can access on TVs; and as overlays that work as a sort of atmospheric layer over some of the narrative parts of the game.

Alan Wake 2 pushes this approach even further: there are some full-screen live-action scenes, but they are relatively few. Most of the time, live-action footage is overlaid over the game world, like in Control, but with even more inventive ways to mix the two: a lot of the live-action material feels like a dreamy layer over the reality of the game, in a strange reversal of real and imagined. The priority is constantly to blend every element seamlessly: Alan Wake 2 is a very impressive-looking game that is not afraid to look “dirty”; filters, film grains, light leaks and mist are often deployed to immerse the player into a textured world that feels immensely cohesive.

Music is also a massive part of this: since the first Alan Wake, Remedy has commissioned artists to create original songs for their games, and these are also often found in the middle of the game world, adding an element of immersion and three-dimensionality to the worlds they create.

Consistency is cinematic

A fundamental element to immersing viewers in a cinematic space is consistency. One of the main jobs of filmmakers is to create a consistent piece of art: like music, cinema is a language that is unforgiving about breaking its spell. A lot of the workflow behind movie production is specifically geared to guarantee consistency. The job of the script supervisor is to make sure that the production and the script line up with each other, and there are continuity photographers in many big movies, working for the same goal. Professional gear for video and film - cameras, light, audio equipment - is not built to just give the best possible image quality; it also needs to guarantee absolute control in every aspect of production, to make sure that it’s possible to keep consistency between different shots, and for the entire project.

The skeuomorphic approach of Alan Wake 2 and Immortality is cinematic exactly for the same reason: these games do their best to never break immersion and consistency. Most games don’t care to do that.

Emergent Cinema

Video Games is a very broad term. Books can contain fiction, essays, educational text, illustrations, and photographs, but their mechanics are largely the same, and the same can be said, to different extents, for movies, music, and paintings. However, two pieces of art defined as video games can function in ways that can be extraordinarily different from each other: Tetris, Super Mario, Civilization and Immortality are all video games, but they interact with the player in radically different ways.

So I don’t think it’s unfair to look into Alan Wake 2 and Immortality and see them as examples of what we can think of as Emergent Cinema; works that use cinematic language while not constrained by a set structure, able to grow and change from session to session with the actions of the players. This is not even a new phenomenon: the language of cinema has been used in video games for decades, even when the graphics were very simple. Elements of framing, editing and sound design that were borrowed from movies can be found in technically simple games from, at least the 1980s.

But in these two games, we see an embrace of the cinematic language that goes beyond what we see even in most movies.

They go beyond what most video games with wonderfully executed cut scenes strive for. The Last of Us, for example, uses cinema very well in its narrative, but when it comes to playing, the relationship between games and cinema is mostly severed. The two do not meet. Hideo Kojima is one of the creatives that is consistently working with Emergent Cinema, and one of its next projects, OD, seems to want to go even further in that path. That said, definitions are always a coarse method of understanding, but they do have some value.

So, Ebert was very wrong (he was also very wrong about Blue Velvet. But he was spot on about many, many other things). Not only video games are art, but video games and cinema are very much compatible. It will be fascinating to see how much further the two can keep dancing.